It has become comical how often the “most important election of our lifetime” phrase is used and abused. My colleague Andrew Kauders was recently elected to his village council and I’m quite sure it was the most important election of his constituents’ lifetimes… or at least, it was important to Kauders.

Tomorrow is Election Day in the Commonwealth of Virginia—my home—and I’ve certainly been asked by the media and others to consider the governor’s race a defining moment in our history. For those of us swamp creatures who work inside the Beltway, what is perhaps most intriguing about this election is the game of setting expectations. Odd-year elections have almost always generated outsized interest and attention but this one race seems particularly amplified given the debates being had within the Democratic party and the race’s potential as a referendum on the first 285 days of unified Democratic control of Washington.

Presidents Biden and Obama, Stacey Abrams and other party leaders have made trips to the Commonwealth to campaign for the Democratic candidate for governor, former Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe. That seems like a lot of firepower when Biden won Virginia by 10 points just a year ago and the Commonwealth hasn’t supported a Republican at the top of the ticket since 2009. Republicans had their “dream” gubernatorial candidate last election and still lost by 9 points. So, what will we learn tomorrow and what does it all mean? Not much.

If Republican candidate Glenn Youngkin wins, Democratic pundits will point to his self-funded $20 million of the $57 million campaign coffer and his balancing act on Trump as the formula for his success. If McAuliffe wins, Republican pundits will point to his time as governor and the increasingly blue color of the state. So if either outcome is easily explained, why are the expectations being raised so high? Because this election WILL effectively kick off the race to the 2022 midterms where both chambers of Congress are up for grabs.

An unmistakably bad habit of Washington is to focus on the next election almost immediately after the last vote from the previous election is counted. The evenly divided Senate and razor-thin, three-seat Democratic majority in the House reveals the precarious nature of power these days. But as fall comes to Washington, there is something in the air that is causing a chill among Democrats – a seemingly inevitable conclusion that they are almost certain to lose control of at least one chamber of Congress in t-minus 13 months.

Regardless of what happens in Virginia tomorrow, history is not on the side of Democrats. Over the past 100 years, the president’s party has gained seats in the House in only three out of 25 midterm elections (12 percent). Each of these three trend-breaking elections must be studied individually for context.

- In 1934 (FDR’s first term), Democrats gained nine seats in the House and secured a supermajority in the Senate in the midst of the Great Depression. Prior to 1934, the president’s party had failed to gain seats in any midterm election since the Civil War.

- In 1998, Democrats gained five seats in the House but did not gain a sufficient number to claim the majority. The election took place in the middle of President Clinton’s second term and was widely seen as a rebuke of the House Republican majority and its pursuit of impeachment. Clinton’s approval rating was in the high 60s prior to the election.

- In 2002, Republicans gained eight seats in the House during a post-9/11 America that was dominated by security concerns. Bush’s approval rating was in the high 60s prior to the election.

At no point in his presidency has Biden enjoyed an approval rating above 60 percent so while not impossible, it would seem likely that the 2022 midterm election will cost the Democrats their slim majority in the House. More recent history for first-term presidents further illustrates the trend that President Biden will be fighting against:

In 1994, during President Clinton’s first midterm:

Democrats lost 52 House seats

In 2010, during President Obama’s first midterm:

Democrats lost 62 House seats

In 2018, during President Trump’s first midterm:

Republicans lost 41 House seats

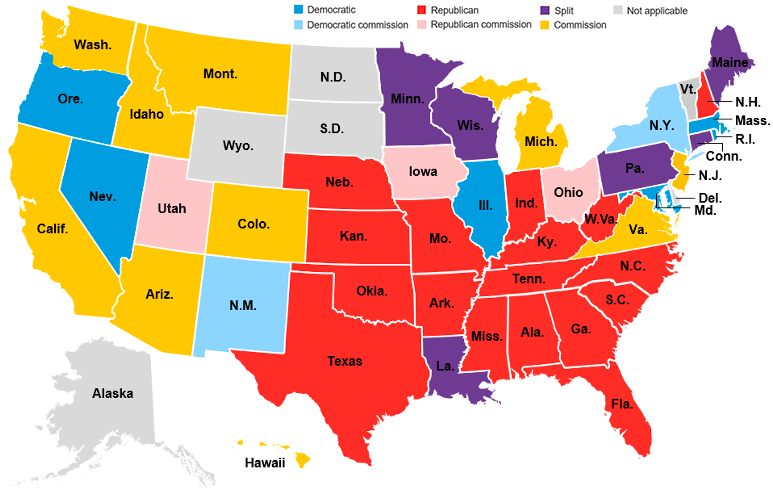

Beyond these historical trend lines, President Biden and the Democrats will also face a challenge that comes only once a decade – redistricting. With the results of the decennial census collected, states are currently working through their respective processes to draw new lines for congressional districts in advance of the 2022 midterm. Based on population trends over the past decade, traditionally GOP-dominated states like Texas, Montana, North Carolina and Florida all gained seats while traditionally Democratic-dominated states like California, Illinois, Michigan, and New York all lost seats. What gets even more concerning for the president and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) is that the mechanism to draw new lines varies from state to state and the failure of Democrats to extend their 2020 federal election gains into state races means that many states will have unified Republican control of redistricting. The result? Unfavorable maps for House Democrats. Recent projections by political analysts at the Cook Political Report suggest Republicans will likely gain a net two to five seats based on redistricting alone. That’s before you get to the traditional midterm penalty described above.

Who Controls Redistricting?

Source: Bloomberg

There’s a lesson here. Virginia’s off-year gubernatorial election is important to me and to my fellow Virginians. But those looking for existential signals as to the direction of the country and the mood of the electorate should maybe stick to historical trends and approval ratings before pivoting and prognosticating on the most important election of our collective lifetimes—the next one.

Dave Oxner is a managing director at Cogent Strategies and a resident of Arlington, Virginia. Dave spent a decade on Capitol Hill working for the staffs of the House and Senate Banking Committees before serving as a managing director and head of federal government relations for the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA). For Dave’s complete bio, click here.